In 1828 the Cherokees were not nomadic savages. In fact, they had assimilated many European-

His political career destroyed because he supported the Cherokee, he left Washington D. C. and headed west to Texas.

By 1835 the Cherokee were divided and despondent. Most supported Principal Chief John Ross, who fought the encroachment of whites starting with the 1832 land lottery. However, a minority(less than 500 out of 17,000 Cherokee in North Georgia) followed Major Ridge, his son John, and Elias Boudinot, who advocated removal. The Treaty of New Echota, signed by Ridge and members of the Treaty Party in 1835, sealed the fate of the Cherokee. In 1838 the United States began the removal to Oklahoma, fulfilling a promise the government made to Georgia in 1802. Ordered to move on the Cherokee, U. S. General Wool resigned his command in protest, delaying the action. His replacement, General Winfield Scott arrived in Georgia on May 17, 1838 with 7000 men. Early that summer General Scott and the United States Army began the invasion of the Cherokee Nation.

In one of the saddest episodes of our brief history, men, women, and children were taken from their land, herded into makeshift forts with minimal facilities and food, then forced to march a thousand miles(Some made part of the trip by boat in equally horrible conditions). Under the generally indifferent army commanders, human losses for the first groups of Cherokee removed were extremely high. John Ross made an urgent appeal to Washington to let him lead his tribe west and the Federal Government agreed. Ross organized the Cherokee into smaller groups and let them move separately through the wilderness so they could forage for food. Although the parties under Ross left in early fall and arrived in Oklahoma during the brutal winter of 1838-

Ironically, just as the Creeks had murdered Chief McIntosh for signing the Treaty of Indian Springs, the Cherokee murdered Major Ridge, his son and Elias Boudinot for signing the Treaty of New Echota. Chief John Ross, who valiantly resisted the forced removal of the Cherokee, lost his wife Quatie in the march. And so a country formed fifty years earlier on the premise “...that all men are created equal, and that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, among these the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness..” brutally closed the curtain on a culture that had done no wrong.

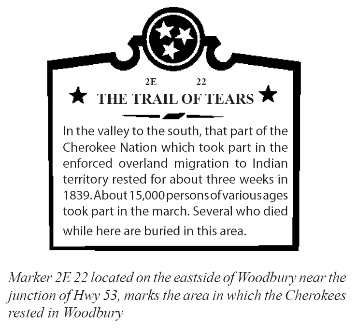

The forced removal of the Cherokee Nation from their homeland in 1838 found thousands of saddened and weary Cherokees passing through Woodbury on The Trail of Tears. Heartbroken and allowed only what personal possessions they could carry, many died on the trail before reaching Fort Gibson.

Copyright © All rights reserved. Made by Jim Gibbs. Terms of use | Privacy policy